Bitperfect 3 2 0 M

adminApril 28 2021

Bitperfect 3 2 0 M

When seeking to convey what the DirectStream achieves with high resolution source material you can never afford to ignore the garbage-in garbage-out principal. High resolution implies that we are talking about source material which rises above and beyond the performance delivered by lower-resolution source material, by which we must assume in turn we are referring to Red Book CD program material. Extending this argument further, it means that we are obliged to confine ourselves to source material of impeccable pedigree. It also follows that, unless we spend most of our time listening to DACs of the highest possible pedigree (which I have at times had the opportunity to do), when we hear exceptional playback of an exceptional recording we generally don’t have a context in which to place a qualitative assessment of what we hear. So in my description of what follows, bear that in mind.

- Bitperfect 3 2 0 Motor

- Bitperfect 3 2 0 M 59 X

- Bitperfect 3 2 0 Model

- 3 & 2 Baseball Shawnee Mission Ks

Bitperfect 3 2 0 Motor

First up, “Quiet Winter Night”, a folk-jazz album by the Hoff Ensemble, from Morton Lindberg at 2L in Norway. This is a 24-bit 352.8kHz (so-called DXD) recording, which is the format in which the original recording was made. 2L makes all of their recordings available in this format if that is what you want. I know of nowhere else where you can purchase the entire catalog of a no-compromise audiophile label in what is truly the Original Studio Master format. They also make available a huge selection of free downloads in a bewildering array of formats, including multi-channel, DSD, and original studio master DXD. Since the DirectStream does not support 352.8kHz PCM, BitPerfect downsamples it to 176.4kHz. The sound is effortless and spacious, having been made in the reverberant soundstage of a small church in Oslo. The instruments are all acoustic, apart from a Strat, and are grouped tightly together. The recording has a “live” feel, although there is no audience. It has a slightly bass-heavy ambience, which to my ears is typical of 2L. Perhaps bass-heavy is wrong. Maybe I mean bass-weighty. Because the microphones are very close to the instruments, and there is little in the way of studio adulteration going on, I think they naturally pick up more of the “weight” of the bass drum and double bass than you would normally hear from a typical listening position. But in any case the DirectStream does a terrific job of presenting the individual instruments and voices, locating them precisely in space. The percussion in particular is presented with a lightness of touch and clarity of texture, but with appropriate weight in the bass.

BitPerfect runs on the Mac platform only, and is only available directly from the Mac App Store (click Here.). OS X 10.11.6 & iTunes 12.4.2.4 Your Competitors are your Best Friends. Dec 29, 2020 Payout Date: 2020-12-29 13:41:00 ID: 357880432 Received Payment 12.2 USD from account U25364613. Memo: API Payment. Withdraw to bitpump from bitperfect.top.

I send the Amazon Music HD stream from the App direct to my good old Sonos Connect (S1). 16-bit, 44,1 kHz/48 kHz is possible, 24-bit, 44,1 kHz/48 kHz only with the new Sonos Port (S2). Add.: My TOPPING D10s DAC, connected to the USB output from my old S8 phone, shows 192 PCM and works without. Announcing BitPerfect v3.1.2. Today we announce the release of v3.1.2 of BitPerfect. This is primarily a maintenance release which addresses a specific problem where BitPerfect is unable to play to AirPlay devices under macOS High Sierra (i.e. This is a workaround rather than a proper solution.

“Résonance” is a recording of solo Viola Da Gamba music by Nima Ben David, from Todd Garfinkel’s MA Recordings. I believe the original master recording was made in DSD, and what I have is a 24-bit 176.4kHz conversion. This recording is quite honestly like being in an intimate highly reverberant studio space with the performer. Ms Ben David is right in front of you, so much so that getting the volume absolutely correct within 0.5dB is crucial to making it sound right. The scrape of the bow across the strings is captured cleanly. The tonality of the instrument is wonderfully present, and, try as I might to listen analytically to the sound, I find myself being drawn inexorably into the music. The Viola Da Gamba is a predecessor of the ‘cello but with a sound which is at once less refined, with some of the weighty tone of a double-bass, but in the hands of Ms Ben David ethereally expressive. And in the hands of the DirectStream, there is little to want for in the sound. The DirectStream’s magical bass was made for music like this.

“Meet Me In London” by Antonio Forcione & Sabina Sciubba, produced back in 1998 by Naim Records, is probably the one “Audiophile” record that truly stands up on its own two feet as a musical experience. It is a collection of covers and standards that showcase Sciubba’s poised and controlled vocal, with Forcione’s dexterous acoustic guitar work, backed up by delicious bass, and occasional other musicians as required. The recording was magnificently captured by Naim, and remastered specially for the 24-bit 192kHz digital download which I have. The DirectStream reproduces this recording beautifully, with the texture and dynamics of Forcione’s guitar work a particular joy to listen to. The bass is wonderfully tasty, with real presence and weight. Sciubba’s vocal is easy on the ear and shows remarkable restraint in terms of dynamic compression, but some compression is inevitably there, and the DirectStream makes it plain if you want to go to the trouble of listening for it. I feel I want to use the word “presence” here again. This is emerging as one of the core characteristics of the DirectStream – it has consistently great “presence”.

I have an odd track – I have no idea where it came from, or who the performers are – but it is a beauty. It is an excerpt from Copland’s “Fanfare For The Common Man”, and was recorded by someone who had a wonderful idea: “Why don’t we do a proper job of capturing those drums?”. Both bass drum and tympani are prominently featured on this recording, and the DirectStream gives free rein to both, limited only by the bass response of my speakers which doesn’t go down much below 28Hz (and neither does my room, for that matter). But when the bass drum strikes, it has an enthrallingly accurate and detectable pitch, something that I have previously only heard before on seriously good headphones, such as Tim’s Stax SR009s. The bloom and decay are wonderfully accurate.

Moving on to DSD. In terms of its specifications, what the DirectStream offers that its predecessors did not, is DSD support. I have left this aspect until last, because I don’t want to over-emphasize its importance. While DSD is at the core of how the DirectStream functions, I would not wish to suggest that it should only be of interest to those with a DSD collection. Far from it – it is a high-performance DAC that happens to do DSD. But its DSD performance still needs to be examined.

Bitperfect 3 2 0 M 59 X

Let me review what I think of DSD at this point in time, recognizing that this a moving, evolving target. For me, the bottom line is that the best sounds I have ever heard have been produced by DSD. At BitPerfect we are quite involved in format conversions between DSD and PCM. We have found that the very best DSD-to-PCM conversions we know of – those produced by our DSD Master product – can be very, very close to their DSD originals. The differences are really quite subtle. We can also do it the other way round – make conversions from PCM originals to DSD – but the best quality PCM-to-DSD conversions are still those made by professional third party software such as Weiss Saracon.

An interesting thing happens when we make PCM conversions from two types of DSD recordings. The first type are original DSD recordings that have never seen PCM, while the second type are DSD conversions from a PCM master. What we have found in the past is that PCM conversions made from “pure” DSD masters (i.e. the first type) are not quite as good as the DSD originals, whereas those made from “impure” DSD masters (i.e. the second type) can be much harder to distinguish from the DSD master. This suggests that a certain “PCM-ness” may be imprinted upon a recording whenever it enters a PCM format, and that once having acquired this “PCM-ness”, it can never again regain what you might call its “DSD-ness”. All very wishy-washy, I know, and not at all scientific (although I do have a rational basis for making that argument). And given that all this was determined exclusively using the Light Harmonic Da Vinci Dual DAC, it is far from conclusive either. But I wanted to mention it, because one of the things I want to accomplish with the DirectStream is to see if the same sort of behaviour can be evinced using it. And just to be clear, I am only going to report preliminary findings in this post. We’ll be doing a lot more work with the DirectStream in this area down the road, and may report on that later if I come up with anything interesting.

In comparing PCM and DSD versions of the same track, how can you avoid comparing Apples and Oranges at some point? Unless you have access to detailed information concerning how the different versions were mastered, how do you know that what you are hearing is not ultimately a difference in the mastering that you end up ascribing to a component in the review system? To attempt to minimize these issues, I set about using DSD Master to make a number of PCM conversions from a selection of DSD tracks that I have, and comparing what I heard from them. That way, the only differences inherent in the source material are those arising from DSD Master’s ministrations, which, if nothing else, are at least known. In each case the PCM versions were 16-bit 44.1kHz, 24-bit 88.2kHz, and 24-bit 176.4kHz, and all were in Apple Lossless format. The DSD tracks were a mixture of “first-type” and “second-type” DSD64 recordings; mostly the latter since the true provenance of a DSD recording is actually desperately hard to establish conclusively.

Bitperfect 3 2 0 Model

I don’t have the time to go into details but the results were all remarkably consistent. First of all, the differences – from CD all the way up to DSD – were much smaller than I expected them to be, and the most noticeable of these differences was moving up from CD to 24/88.2, which is probably due to the step up in bit depth. With each upward step in format resolution the same two general things were observed to happen. The bass got cleaner and firmer, and the detail resolution of instruments across the spectrum improved. The soundstage imaging got crisper, and everything just seemed to acquire that extra smidgeon of presence. However, the difference between 24/176.4 PCM and DSD was most often too difficult to reliably detect. I suppose I should be making a big deal of that – how DSD Master produces PCM conversions which are close to indistinguishable from DSD – and yes these conversions are good, but I don’t think that’s the whole story here.

The bottom line is that the DirectStream produces exceptionally good sounds playing DSD material, but it also produces virtually indistinguishable sounds playing DSD Master’s PCM conversions of the same material. If pushed to get off the fence here, I would suggest that the DirectStream’s DSD processing may be at the root of this. Using the terminology I introduced earlier, it sounds to my ears as though the DSD processing in the DirectStream may be introducing “PCM-ness” into the DSD data stream. We should not lose sight of the fact that there is a lot of signal processing going on in the DirectStream, just as there is in other DACs built using common commercial DAC chipsets. Each of those chipsets uses its own proprietary implementations of those signal processing algorithms, and DirectStream merely has its own. This signal processing is wickedly complex, and does not yield to a few pithy sentences. It is also an area in which great progress will continue to be made, aided by the inexorable advancements which will continue to be made in signal processing technology.

In summary, the DirectStream is very nearly the best DAC that has ever passed through my system, yielding only to the Light Harmonic Da Vinci Dual DAC. At $6,000 it is far from cheap. But if you are willing to consider spending that kind of moolah, the DirectStream handily outperforms anything I have heard for anything short of seriously silly money. And since PS Audio has a pretty comprehensive worldwide dealer network, the prospects of being able to audition one locally are better than for a lot of its serious competition.

As a kind of coda to this review, I have implied that the Light Harmonic Da Vinci Dual DAC is better than the DirectStream, and indeed it is. I lived with one for the best part of a year. But it comes in at $31,000 last time I looked. What do you get for the extra $25,000? Simply put, the Da Vinci places the performers right there in the room with you. Sonic textures are so convincingly real. If you can describe the DirectStream’s sense of presence as exceptional, then that of the Da Vinci is quite uncanny. It can make you stop and turn your head when you are elsewhere in the house, which is something you have to experience to believe, and is a party trick the DirectStream cannot quite pull off. It is possible, though, that the DirectStream’s bass might be even better than that of the Da Vinci. Listening to DSD on the Da Vinci can be heartbreakingly good, just as the Linn Sondek LP12 was, in its way, when it burst on the scene nearly 40 years ago. The Da Vinci Dual DAC illuminates differences between PCM and DSD which the DirectStream apparently cannot. Granted, those differences probe deeply into the realm of diminishing returns. So if a Da Vinci Dual DAC costs $31,000 how much is a DirectStream worth? I would suggest that $6,000 sounds more and more like an absolute steal.

3 & 2 Baseball Shawnee Mission Ks

At BitPerfect we needed a reference-quality DSD-compatible DAC, and, without mentioning names, the ones we had to hand were proving not be up to the standards we were hoping for. To a certain extent, this is a self-fulfilling prophesy. At the end of the day the differences between DSD and PCM, while real enough, are actually quite small. On the amazing Da Vinci Dual DAC (which costs over $31,000) it certainly is subtle, although real enough that once you’ve heard it you want more of it. So at the sane end of the price spectrum, where should one be setting realistic expectations?We found out, eventually, that we weren’t going to find what we needed at the truly sane end of the price spectrum, so we set our sights a little higher. Talking to Paul McGowan of PS Audio, we decided that their new DirectStream DAC, which was still in development at the time, was in all likelihood what we needed, so we committed to purchase one of the first production models. I have been listening to it for the last week. I’m listening to it as I type. I’ve been doing little else for the last week. I don’t normally do product reviews - I am not a professional reviewer - but I felt that in this instance the effort was probably justified. Please read on.

The PS Audio DirectStream DAC is not cheap. At $6,000 it is priced at a point which all of my friends would unhesitatingly label “insane”. But in the world of high-end audio, the market to which it is targeted, it has the potential to be classified as a bargain. Provided it delivers on the hype, that is. C’mon, you already know it does, because otherwise I wouldn’t be writing this! But let’s play along anyway, and pretend you haven’t already figured out that the butler did it.

The DirecstStream’s design eschews the conventional wisdom regarding the design of a high-end DAC, which says you go out and buy a chip-set from one of the established vendors such as ESS, TI, and Wolfson, and build yourself a DAC around it. Rather like you would build a computer, having chosen an appropriate CPU from Intel’s catalog. PS Audio has taken a different tack. They have avoided using a DAC chip entirely, and have built their entire core converter functionality around a FPGA which switches the output voltage between two seriously stable voltage levels, representing the ‘1’ and the ‘0’ of a DSD bitstream. This is quite a smart approach, but it requires every single input data stream to be converted to a 1-bit format, and the one they have chosen is 1-bit / 5.6448MHz, otherwise known as DSD128.

As it happens, the chip-based solutions don’t quite do it this way. Instead of a 1-bit format, they use a 3-bit, 4-bit, or even 5-bit format, and there is a good reason for doing that. The devilishly complex Sigma-Delta Modulators (SDMs) used to perform these conversions are fundamentally unstable when configured with a 1-bit output. This instability can be avoided entirely by using a multi-bit output format. But the actual D-to-A conversion using those multi-bit bitstreams is more complex. In effect, PS Audio has traded the electronic complexity of a multi-bit high-speed D-to-A converter for a design approach they can get their considerable electronic design chops around. All that needs to be done is to navigate a way around the 1-bit SDM instability problem. As it happens, there are various techniques to mitigate this problem, although it cannot be conclusively eliminated. But by taking the right measures it can be beaten into submission, otherwise SACD/DSD couldn’t be made to work.

Inside the DirectStream, all input formats - DSD128 included - are converted to a single 30-bit 10MHz format, and from there converted to DSD128 which is fed to the core converter. There are a couple reasons for this. The first is that digital volume control can be easily implemented in this intermediate stage. The second - behind which hide an advanced degree’s worth of technical matters - is that the analog output filters in the output stage assume a certain implementation of the DSD128 data stream to which an arbitrary incoming data stream might not adhere. [My thanks to Ted Smith of PS Audio for clearing that up for me.]

Paul McGowan has created a lot of hype around the DirectStream through his intriguing claim that it manages to extract more musical information from ordinary CDs (read 16/44.1-formatted music) than any other DAC. By and large, this claim seems to be backed up by other people who have heard the DirectStream for themselves. So a significant part of this review will be devoted to assessing its Red Book (16-bit, 44.1kHz PCM) performance, although don’t expect me to pronounce one way or the other on McGowan’s claims.

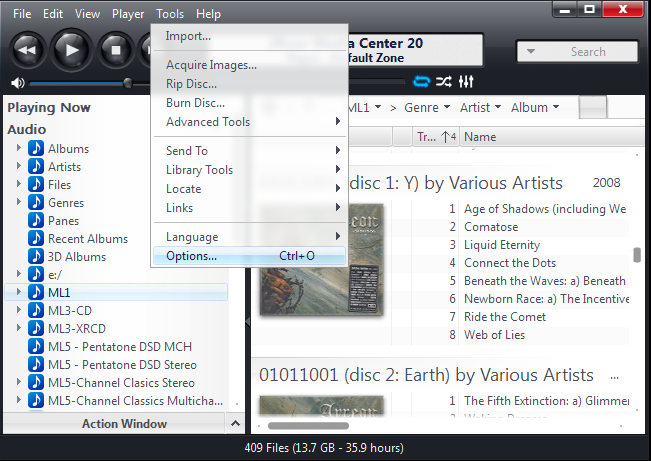

My test setup was as follows. The DirectStream was fed by a 2013 base-spec Mac Mini, running OS/X 10.9.3 with iTunes 11.2.1 and BitPerfect 2.0.2 (a pre-release beta). The DirectStream was fed into a Classé CP800 preamplifier which in turn fed a Classé CA2300 power amplifier. The loudspeakers were B&W 802 Diamonds. The Mac Mini used a PS Audio Jewel Power Cord, and the USB cable was a 1m Nordost Blue Heaven. All other Power Cords, plus all the (balanced) interconnects were BitPerfect Digital Precision products. The speaker cables were dual (bi-wired) runs of Cardas Golden Cross. Not only the DirectStream, but also its Power Cord and its interconnects, were all new and unused and so a period of break-in was required.

Powered up for the first time, and prior to any break-in, the sound was noticeably thin, brittle, and edgy. This could be down to the DirectStream or any of the brand new cables (and I have little interest in finding out which was responsible for what), but nevertheless you could tell immediately that here was something with serious detail in its sonic presentation. I set it up for a period of continuous break-in which I was prepared to last for at least a good week. In fact the improvement over the first 24 hours was quite dramatic, and by the end of the fourth day the previous 24-hour period seemed to have wrought no significant improvements, so at that point serious listening commenced. If significant break-in over a time frame of weeks should occur, I might report on it later.

PS Audio makes a point of recommending that you connect the DirectStream directly to the inputs of your Power Amplifier for a potentially ideal listening experience. It took me until the sixth day of listening before I got round to that, but the result was so immediately and obviously superior that this instantly became my preferred configuration. This entire review uses the DirectStream connected directly to the Power Amplifier’s inputs.

Before going on, there are a couple of matters specific to BitPerfect users. The first is that DirectStream only supports PCM sample rates up to 192kHz. However, in order to deliver DSD128 support, it must also support a PCM stream format at 352.8kHz which it duly announces to OS/X. However, if you send it a true 352.8kHz PCM data stream it does not play properly. Therefore it is important to set BitPerfect’s “Max Sample Rate” to 192kHz. I would also check “Upsample by Powers of Two” so that any DXD (24/352.8) tracks which you may have - and I have quite a few - will be downsampled to 176.4kHz rather than 192kHz.

The second matter relates to volume control, and requires an extended discussion. First of all I used BitPerfect’s Volume Control (the slider in the menu bar drop-down menu), which addresses the DAC’s USB-accessible volume control. While this does indeed control the volume it has some unexpected behaviour. The first is that it operates independently of the DirectStream’s own volume control, and cannot be addressed within the DirectStream itself. The second is that when used on a DSD track it causes the volume to be muted. BitPerfect Users used to using the volume control via its keyboard shortcuts may find this behaviour slightly annoying. According to Paul McGowan this behaviour arises because the XMOS USB receiver is unexpectedly acting upon the USB-delivered volume control commands. At this point, I am not sure which direction PS Audio will take when they get around to addressing this issue. Having a USB-accessible volume control is usually quite desirable in a Computer-based audio system, and I hope they will take that into account.

A personal irritation is that the DirectStream’s internal volume control is calibrated on a 0-100 scale, with 100 representing 0dB and each ‘1’ dialing in 0.5dB of attenuation (and ‘0’ being muted). I personally prefer to see the dB attenuation scale indicated (which is actually more common these days). In comparison, 0-100 is a bit like a car’s speedometer calibrated as 0-100%. “Honestly, officer, I was only doing 55%!!”. But I appreciate that other users may have a different perspective.

Build quality of the DirectStream is everything you would expect from a $6,000 component. Mine is finished in silver (black is an option), and has an unusual glossy piano-black top surface which looks very crisp, and as far as I can tell has a primarily cosmetic function. Sitting on top of my equipment rack it also ties in visually with my piano-black 802 Diamonds. For a DAC it is surprisingly heavy, not least because its analog output stage unusually uses a transformer (although I have not opened it up to see how big the transformer is). The heft also suggests a generously-specified linear power supply. Given PS Audio’s expertise in audio power supply, this would not be in the least surprising. The front panel is bare except for a small touch-panel display. This display can be dimmed if preferred (turned off, actually) using a button on the supplied remote control, but having done so I could not un-dim it without powering down the DirectStream. Am I being unfair by observing that the remote itself is a bit plasticky, in comparison with the hewn-from-a-solid-billet look and feel of the DirectStream itself? The similarly-priced Classé CP800 has a remote that might break your toe if you were to accidentally drop it. All things considered, the DirectStream’s physical presence is fully consistent with its price tag.

So how does it sound? Click here and let's find out.

Bitperfect 3 2 0 M